THE recent NST Online report detailing how foreign nationals are allegedly camping out at Kuala Lumpur International Airport (KLIA) for days in hopes of entering Malaysia through manipulated immigration processes is not just an embarrassing administrative blunder, it is a clear symptom of a much deeper institutional illness.

At the heart of this disturbing trend lies the practice of “counter-setting,” wherein certain immigration counters are allegedly manned by officials who can be counted on to facilitate questionable entries.

This manipulative and unethical arrangement allows individuals who may otherwise be denied entry into Malaysia to slip through the cracks, raising significant national security and reputational concerns.

This is not merely a logistical loophole or operational inefficiency, it reflects a profound lack of professionalism and a major deficit in institutional integrity.

Immigration officers are entrusted with safeguarding Malaysia’s borders, not compromising them for profit, favours, or convenience.

The fact that some travellers are reportedly willing to sleep at the airport for days, waiting for the “right counter” to open, is damning evidence of systemic rot and a deeply compromised enforcement culture.

If left unaddressed, this issue will continue to erode both public trust and Malaysia’s international credibility. It sends a dangerous signal that immigration control is negotiable and vulnerable to manipulation.

In a region already grappling with complex challenges such as human trafficking, transnational crime, and irregular migration, Malaysia cannot afford to be seen as a soft target or weak link.

Moreover, in an age of increasing global scrutiny, these lapses cast serious doubt on our ability or willingness to uphold international human rights standards and border management obligations.

This scandal has implications that go far beyond KLIA, it touches the very core of our nation’s governance and moral standing.

Thus, traditional remedies such as internal memos, staff reshuffles, and occasional disciplinary actions have clearly failed.

What is needed now is a bold, comprehensive, and technologically integrated reform agenda that prioritises transparency, integrity, and long-term institutional resilience.

Countries like Canada and the Netherlands have implemented AI-driven systems at their major international airports to track anomalies in passenger flows and officer conduct.

These systems can analyse real-time data to flag unusual behaviours such as repeat visits, patterns of evasion, or clustering of questionable approvals at specific counters.

Therefore, Malaysia must invest in similar predictive tools that provide supervisors with alerts on potential abuses. A data-driven culture of prevention not just punishment must become the norm.

Furthermore, to eliminate manual manipulation of counter assignments, a digitally randomised assignment system should be used, encrypted and tamper-proof.

The United Kingdom’s Border Force, for example, uses secure digital rotations to ensure that officers are periodically reassigned without prior notice, limiting the ability for syndicates to “place bets” on insider help.

This system must also log every change and allow for third-party audits. Transparency and record-keeping should become tools of deterrence.

Airports in Singapore, Germany, and Japan utilise facial recognition technology paired with behavioural analytics to identify both passengers and suspicious staff movements.

Malaysia can adopt similar technologies to track who accesses sensitive systems and how immigration decisions are made.

A secure log of each officer’s activity, paired with a machine-learning model of risk behaviour, can help in building real-time dashboards for internal auditors.

Most importantly, an empowered autonomous Internal Integrity Unit modelled after the US Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Inspector General should be established to conduct undercover operations, sting investigations, and integrity tests.

This body should report directly to Parliament or an independent committee, not the department it investigates. Regular public reporting will strengthen accountability.

Obviously, the fear of retaliation is one of the biggest barriers to exposing internal misconduct.

Implement a formal whistleblower protection policy, coupled with confidential reporting platforms and incentives for actionable intelligence. Countries like New Zealand and Sweden have robust whistleblower laws that Malaysia can emulate.

For genuine victims of trafficking or coercion, KLIA should include a Temporary Protection Unit run in partnership with NGOs and international bodies like IOM and UNHCR.

This humanitarian facility can assess and provide urgent care to vulnerable individuals including legal aid, shelter, and trauma counselling.

Singapore’s ICA have successfully partnered with civil society to identify and protect victims during the immigration process. Malaysia must do the same, not only as a moral duty, but to break the cycle of exploitation.

Reforming KLIA’s immigration operations is not reinventing the wheel, the playbook exists, and successful models from other democratic societies show us the way forward.

Estonia, known for its e-governance systems, uses blockchain-based tamper-proof logging in immigration records.

Finland uses anonymous peer-review auditing in customs and border protection to ensure decisions can be reviewed for bias or error.

South Korea mandates periodic integrity vetting for all immigration officers, including financial disclosures and psychological assessments.

Malaysia can draw on these examples and tailor them to its own legal and cultural context.

Malaysia has a critical choice to make. We can continue applying cosmetic fixes, hoping the scandal fades from public memory.

Or we can confront the uncomfortable truth that parts of our immigration enforcement machinery are compromised and must be rebuilt, bottom-up, with urgency and honesty.

Ultimately, to act decisively is to reaffirm our commitment to the rule of law, good governance, and human dignity. To delay is to invite further erosion of our national credibility and to put vulnerable lives at risk.

This must be a defining moment for determined leadership and moral clarity. The world is watching. More importantly, so are Malaysians.

This article first appeared on NST.

Past Events

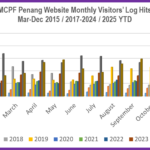

- MCPF Penang Website www.mcpfpg.org Visitors’ Log hits a Monthly Record high of 23.24k in November 2025. Cum-to-date total: 977,865 (March 2016 to November 2025)

- MCPF SPS DLC participates in Camp for Uniformed Bodies at SJK (T) Nibong Tebal

- MCPF Penang engages in Operational Meeting at SMK Mengkuang, Bukit Mertajam to follow-up on CCTV Project Proposal

- MCPF Penang Quartermaster Munusamy Muniandy does an on-site Housekeeping / Maintenance inspection of MCPF Penang Office at PDRM IPK P. Pinang

- MCPF Penang & SPS DLC participates in PDRM’s Launching Ceremony of Amanita Taman Angkat at ADTEC ATM Kepala Batas