While financial institutions continue to invest heavily in firewalls, artificial intelligence and automated monitoring tools, technology alone is insufficient to prevent sophisticated financial crime.

Over the past decade, banks worldwide have embraced automation, artificial intelligence and machine learning to monitor financial flows. These systems can scan millions of transactions in real time, identify abnormal patterns and reduce operational workload. In principle, this represents progress. In practice, however, it has also created a dangerous illusion of security – the belief that technology can independently detect, prevent and neutralise criminal behaviour without sustained human oversight.

Criminal networks do not operate in predictable or static ways. Unlike algorithms, they adapt rapidly, study institutional controls and exploit blind spots embedded in systems trained on historical data. Automated monitoring tools are only as effective as the assumptions built into them. When criminals deploy new techniques or structure transactions to remain just below alert thresholds, technological safeguards may fail to detect wrongdoing.

This risk increases when crimes involve layered strategies combining cyber intrusion, procedural manipulation and insider knowledge.

Criminological research consistently shows that many major financial crimes are not purely technical offences. They are social, organisational and behavioural crimes. Fraudsters exploit not just system vulnerabilities, but also institutional routines, fragmented oversight and human complacency. In many high-impact cases, the threat comes from insiders – individuals with legitimate access who understand how systems work and how irregularities can be concealed within normal transaction flows.

This is where human judgment remains irreplaceable.

Trained professionals can recognise contextual red flags that automated systems may overlook. They can question transactions that appear technically compliant but behaviourally suspicious. Humans are able to connect patterns across departments, accounts and timelines – patterns that may not trigger alerts in isolation but become suspicious when viewed holistically. Technology can assist detection, but it cannot reason, doubt or exercise ethical discretion.

A further concern lies in how fraud units are staffed and positioned within financial institutions. Too often, fraud detection is treated as a purely technical or compliance function rather than a core crime-prevention role. Effective fraud units must be staffed with personnel of high integrity, professional independence and strong ethical grounding. Without these qualities, even the most advanced monitoring systems can be ignored, overridden or deliberately exploited.

Equally important is the need for multidisciplinary expertise. Financial crime today sits at the intersection of law, criminology, accounting, psychology and cybersecurity. Fraud units should not consist solely of IT specialists or compliance officers. They require forensic accountants who understand money trails, criminologists who grasp offender behaviour, behavioural analysts who can detect insider threats, and legal professionals who understand regulatory and ethical boundaries.

This diversity strengthens institutional resilience and reduces over-dependence on any single line of defence.

From a broader criminological standpoint, over-reliance on technology reflects a form of organisational technocracy – the belief that systems can replace human responsibility. When institutions prioritise digital transformation without equal emphasis on governance, culture and accountability, they inadvertently create environments where wrongdoing can flourish unnoticed. Criminals thrive in systems where responsibility is diffused and trust is placed unquestioningly in automated controls.

Ultimately, effective financial crime prevention is not a technological problem alone; it is a socio-technical challenge. Banks must integrate robust digital systems with vigilant human oversight, ethical culture and strong governance structures. Technology should support decision-making, not replace it. Human expertise must remain central in monitoring, interpreting and responding to financial risks.

The lesson from recent events is clear. Firewalls, algorithms and artificial intelligence are necessary tools, but they are not guardians. Without skilled, alert and principled professionals actively overseeing financial movements, no system – however advanced – can fully protect financial institutions or the public.

In the fight against financial crime, humans must remain firmly in the loop.

DATO’ DR P. SUNDRAMOORTHY

Criminologist

Centre for Policy Research

Universiti Sains Malaysia

Past Events

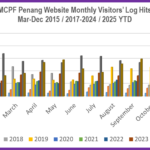

- MCPF Penang Website www.mcpfpg.org Visitors’ Log hits a Monthly Record high of 23.24k in November 2025. Cum-to-date total: 977,865 (March 2016 to November 2025)

- MCPF SPS DLC participates in Camp for Uniformed Bodies at SJK (T) Nibong Tebal

- MCPF Penang engages in Operational Meeting at SMK Mengkuang, Bukit Mertajam to follow-up on CCTV Project Proposal

- MCPF Penang Quartermaster Munusamy Muniandy does an on-site Housekeeping / Maintenance inspection of MCPF Penang Office at PDRM IPK P. Pinang

- MCPF Penang & SPS DLC participates in PDRM’s Launching Ceremony of Amanita Taman Angkat at ADTEC ATM Kepala Batas