The Malaysian government in 2024 paid RM600,000 in compensation to the family of the late Teoh Beng Hock, a political aide who died in 2009 while in the custody of the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission (MACC).

His death, which shocked the nation, was initially classified as a suicide. But years of public outcry, investigations, and legal proceedings pointed to possible foul play and institutional culpability.

Teoh’s case has long symbolised the lack of accountability in custodial deaths involving enforcement agencies.

The government’s compensation, though a step forward, came 15 years after his death. It raises serious questions about timeliness, sincerity, and whether such redress would have materialised at all without sustained public pressure.

Moreover, the amount, while not insignificant, appears modest in comparison to compensation offered in other state-involved deaths – underscoring once again the lack of consistent valuation of life.

Earlier this week, MACC chief commissioner Tan Sri Azam Baki offered a goodwill contribution as a “gesture of compassion” to Teoh’s family for their prolonged pain and suffering. The family however has rejected his offer.

The RM1.5 million ex gratia compensation awarded in 2023 to the family of the late firefighter Muhammad Adib Mohd Kassim reignited public debate over how the Malaysian government values life, particularly in cases where state institutions are perceived to have failed in their duty of care.

While the gesture was welcomed by many, it also highlighted a profound policy vacuum in Malaysia: there is no uniform law, policy, or scale for compensating victims of wrongful or controversial deaths involving state actors.

This raises troubling questions. What determines the amount a grieving family receives? Public outrage? Political relevance? Media coverage?

Tragically, the current system – or lack thereof – suggests that justice in compensation is uneven, reactive, and discretionary.

Malaysia does not have a codified statute or independent commission that determines state liability and financial compensation for lives lost due to institutional negligence, state violence, or failures of enforcement agencies.

Victims’ families are often left with two unequal choices: quietly accept nominal redress or wage long, expensive legal battles against the government.

In most cases where families seek justice, they rely on tort law, suing for wrongful death or negligence. But this involves high legal costs, a burden of proof that is difficult to meet, and years of emotional strain.

While the government does occasionally issue ex gratia payments – as in the case of Adib – these are discretionary, not rooted in law or legal liability, and lack consistency.

In contrast, countries like the United Kingdom and Canada have developed more structured systems for compensating victims of state-related harm.

In the UK, the Criminal Injuries Compensation Authority (CICA) provides financial compensation to victims of violent crime, including cases involving police misconduct, with claims assessed under a transparent, tariff-based system.

Compensation is determined based on the severity of harm, loss of earnings, and other damages, and does not require the conclusion of criminal trials.

In Canada, the provinces administer compensation schemes for victims of crime. In cases involving state wrongdoing, such as wrongful imprisonment or police abuse, the federal and provincial governments have, in several instances, issued public apologies and multimillion-dollar settlements without requiring victims to sue.

For example, Maher Arar, a Canadian citizen wrongfully detained and tortured abroad with the complicity of Canadian agencies, was awarded CAD$10.5 million in compensation and a formal apology. These examples show that structured, transparent, and rights-based approaches not only uphold justice but also reaffirm public confidence in state institutions.

Adib, a 24-year-old firefighter, died in December 2018 from injuries sustained during a riot near the Seafield temple in Subang Jaya, Selangor. His death became a national flashpoint, drawing intense political and ethnic reactions.

In 2019, a coroner’s inquest ruled that his death was due to a criminal act by two or more persons. Yet to date, no one has been charged.

Furthermore, in late 2019, the government awarded Adib’s family RM1.5 million in compensation, presented as a symbol of appreciation and recognition of his sacrifice. The payment was made without court proceedings or a formal finding of state liability and was framed as a moral gesture. But Adib’s case is the exception, not the norm.

Numerous other Malaysians, often from marginalised communities, have died in suspicious or unlawful circumstances involving enforcement agencies.

Unlike Adib’s or Teoh’s families, most have received little or no compensation unless they initiated legal action.

In the case of A. Ganapathy, who died in Gombak police custody in 2021, his family alleged he was beaten while detained, resulting in leg injuries that became fatally infected. A post-mortem revealed severe bruises and internal injuries. His family has filed a RM13 million lawsuit, but no compensation has been paid to date.

Similarly, in 2013, N. Dhamendran died in police custody with visible signs of torture, including stapler wounds and bruises. Though four police officers were charged, they were later acquitted. His family filed a civil suit and received only RM250,000 in 2018 – five years after his death.

Another stark example is the case of Syed Mohd Azlan Syed Mohamed Nur, who died in custody in 2014 after being arrested in Johor. The Enforcement Agency Integrity Commission (EAIC) found evidence of 61 injuries on his body, many of which were consistent with physical assault. Yet no officer was charged and his family reportedly received no compensation.

In a similarly tragic case, Francis Udayappan, who died in 2004 under suspicious circumstances in police custody, became a symbol of alleged custodial abuse and institutional cover-up. After 15 years of legal battle, his mother was finally awarded RM317,000 in 2019. Again, this was not through state initiative, but through civil litigation. The government did not issue any ex-gratia compensation.

These cases point to a glaring disparity. Those who die in controversial circumstances but lack political visibility or mass support often receive less justice and far less compensation.

The lack of consistency in redress is not just an administrative oversight; it is a failure of state accountability. Without a structured system to assess, compensate, and apologise for lives lost due to state or institutional negligence, Malaysia risks deepening public distrust in its justice system.

What’s urgently needed is a comprehensive Victim Compensation Act or the establishment of a National Commission on State Accountability and Redress.

Such a body or legal mechanism should set clear guidelines for when the state must compensate, apply transparent calculations that consider income, dependents, and trauma, and ensure equitable treatment regardless of race, class, or profession. It must also ensure that compensation is not based on political pressure or media attention, but grounded in justice and fairness.

The RM1.5 million awarded to Muhammad Adib’s family and the RM600,000 offered to Teoh’s family should be viewed not as isolated acts of goodwill, but as benchmarks that demand legal grounding and consistency.

If a life sacrificed in the line of duty is worth RM1.5 million, then a life lost in state custody – arguably due to institutional failure – must be valued with equal weight, dignity, and compassion.

Every life matters, not just those that draw headlines.

Malaysia must move from a discretionary and reactive model to a rights-based and equitable framework for compensating victims and families. Because justice – real justice – is not about who gets the most attention, but about ensuring no life is forgotten and no family is left behind.

The measure of a nation’s justice is not in how it rewards the heroic, but in how it treats the forgotten.

If Malaysia is to evolve into a truly just society, it must enshrine mechanisms that deliver both accountability and restitution in a consistent and dignified manner.

DATO’ DR P. SUNDRAMOORTHY

Criminologist

Centre for Policy Research

Universiti Sains Malaysia

Past Events

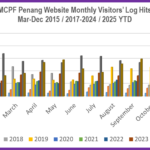

- MCPF Penang Website www.mcpfpg.org Visitors’ Log hits a Monthly Record high of 23.24k in November 2025. Cum-to-date total: 977,865 (March 2016 to November 2025)

- MCPF SPS DLC participates in Camp for Uniformed Bodies at SJK (T) Nibong Tebal

- MCPF Penang engages in Operational Meeting at SMK Mengkuang, Bukit Mertajam to follow-up on CCTV Project Proposal

- MCPF Penang Quartermaster Munusamy Muniandy does an on-site Housekeeping / Maintenance inspection of MCPF Penang Office at PDRM IPK P. Pinang

- MCPF Penang & SPS DLC participates in PDRM’s Launching Ceremony of Amanita Taman Angkat at ADTEC ATM Kepala Batas